The Story of Mankind Part I

The Story of Mankind

The Story of Mankind Part I

The Story of Mankind

The Story of Mankind Part I

The Story of Mankind

The Story of Mankind Part I

The Story of Mankind

Study the lesson for one week.

Over the week:

Activity 1: Narrate the Lesson

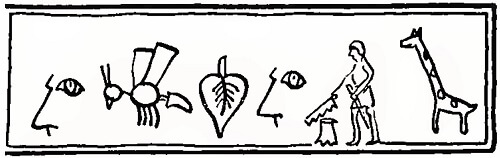

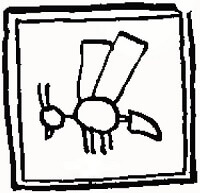

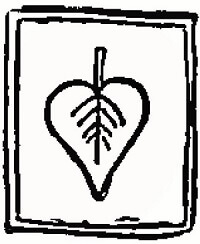

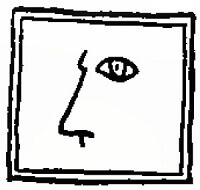

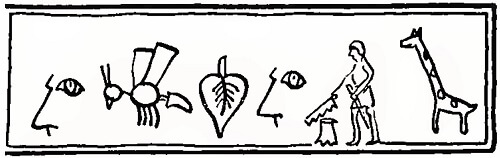

Activity 2: Translate Hieroglyphics

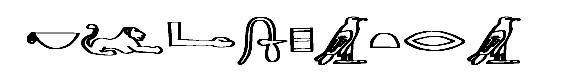

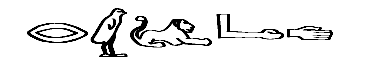

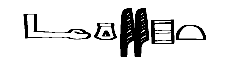

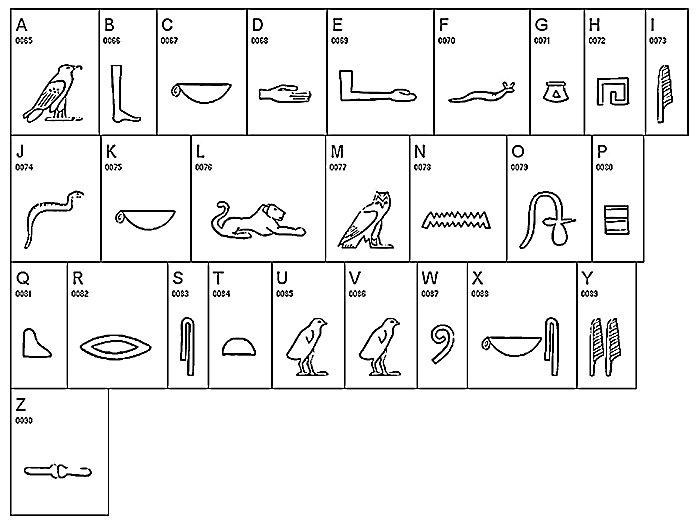

Use the table to translate the following secret hieroglyphic message into English:

Activity 3: Complete Copywork, Narration, and Dictation

Click the crayon above. Complete page 11 of 'World History Copywork, Narration, Dictation, and Art for Third Grade.'

Activity 4: Write a Message in Hieroglyphics

Click the crayon above. Read the below instructions and complete page 12 of 'World History Copywork, Narration, Dictation, and Art for Third Grade.'

Activity 5: Create a Translation Table for the Hieroglyphics from the Story

Click the crayon above. Read the below instructions and complete page 13 of 'World History Copywork, Narration, Dictation, and Art for Third Grade.'

Use a pencil, pen, or charcoal to create your own translation table for the hieroglyphics from the chapter.